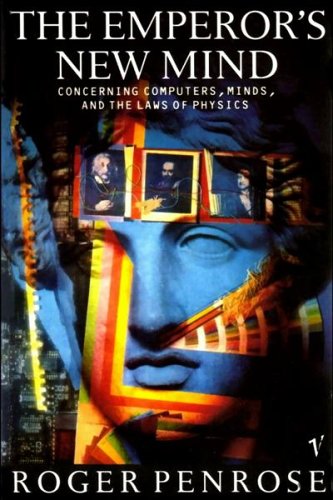

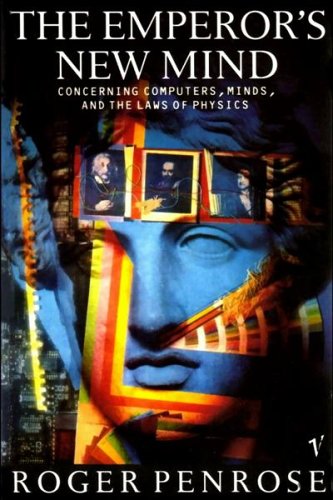

In September 1990 I was living in Oxford, just about to begin my postgraduate study, and I noticed something familiar and unexpected in the window of what was then Blackwell’s Paperback Bookshop on Broad Street:

Roger Penrose’s The Emperor’s New Mind had come out in a Vintage paperback, and I instantly recognised the style of the cover artist. A little later, I saw another very familiar jacket, and asked the staff if I could have one of the large promotional posters they’d had in the window:

I’d been listening to John Foxx’s music since around the time of his album The Garden; I’d come to him via the Midge-Ure-era incarnation of Ultravox, and had discovered the earlier Foxx-era Ultravox and then Foxx’s solo work. Born Dennis Leigh in Chorley, Lancashire, he had studied at art college in Lancashire and later at the Royal College of Art, before starting a band; from the outset he had been involved in the design of Ultravox’s sleeves. Early sleeves (‘RockWrok’ and ‘Young Savage’ around 1977) had employed rough-and-ready collage style that was ubiquitous in punk, but with the first single from their Systems of Romance album, a more refined style had emerged: less of the kidnap-gang and ransom-note style, more of a detached reworking of high European culture.

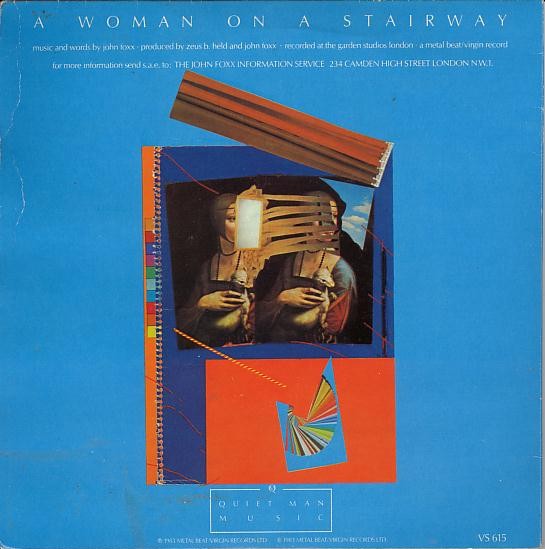

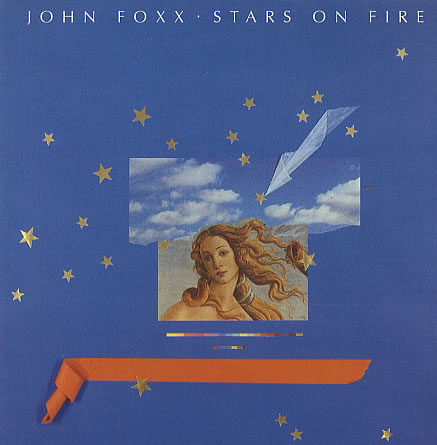

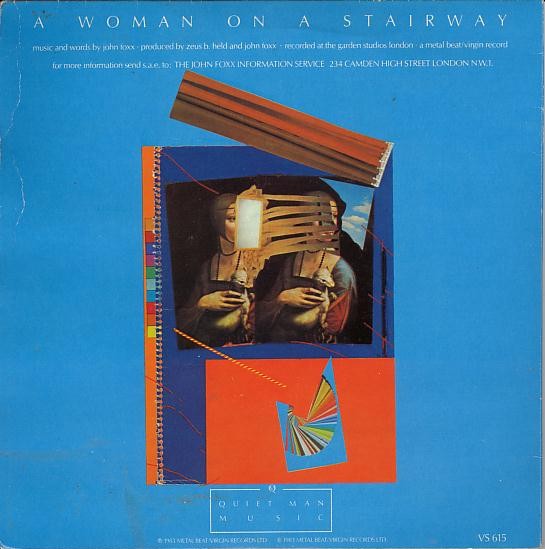

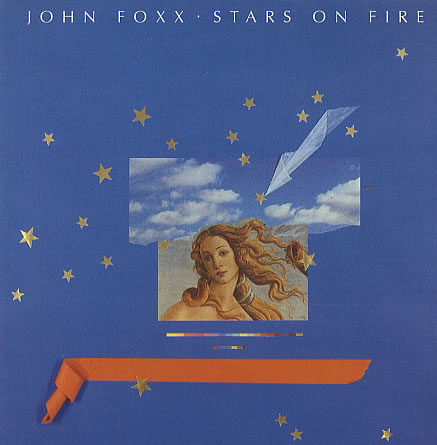

Foxx dropped that style for the stark minimalism of his first solo album, Metamatic, and for the associated singles, but it re-emerged in the sleeve for the single ‘Europe After the Rain’ (1981), and, having been allowed to drop for a few more singles, emerged again for several more singles: the second version of ‘Endlessly’, ‘Your Dress’, and ‘Stars on Fire’.

Dennis Leigh, front cover of Endlessly (second version)

Dennis Leigh, back cover of ‘Your Dress’

Although there are all sorts of different methods being used in these sleeves, they’re united by their sources (Italian paintings, especially Botticelli) and framing elements (the numbers at the edge of ‘Slow Motion’, the colour strips at the edge of of ‘Stars on Fire’) which reference colour-printing quality control or some sort of indexing system.

After ‘Stars on Fire’ and the album from which it was drawn, In Mysterious Ways, Foxx withdrew from the music industry. He lectured on design in the art departments of various universities, and worked as a book-cover designer, under his real name, hence the Penrose and Winterson covers. (A few years years later I discovered that he’d been living a few miles up the road from my parents, in south Oxfordshire; I bumped into a friend from school who had been having French conversation lessons with his wife). My own musical tastes moved on too. The remembered versions of the songs stayed with me, but the relatively commercial production values of the last two albums grated. The early Ultravox material stood the test of time much better.

Much of my D.Phil. involved thinking about the popular science writing of the 1920s, and although Penrose’s book is very different from (say) Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World (1928), the popular science boom that followed Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time was an important element of dialogue between the past and the present. Seeing Leigh’s designs on the covers of both literature and science was a reminder that at some points, literary and popular scientific culture overlapped. At some point in reworking my thesis into a book, Einstein’s Wake, I imagined the sleeve of ‘Slow Motion’ as the ideal image. A crucial argument both in thesis and book concerns the finite velocity of light, and the way it becomes an image for the belatedness of knowledge in modernity. Many expositors adopted Camille Flammarion’s ideal that, seen from a distant point in space, the Battle of Waterloo appeared to be happening in the present moment. The way the image of the woman’s face is spread across space speaks to that idea. The sequences of numbers in the margins also intrigued me, and touched on the idea that our knowledge is relative to our frame of reference; I particularly liked the way that the sequence at the left has a gap in it, as if the frame isn’t quite as reliable as it should be. I was contracted to publish with Oxford University Press, and at that date its jackets were typographically conservative (Roman fonts) and tended to include a small framed image centrally in the page; I liked the way that ‘Slow Motion’ would fit that tradition but also break it; modernist fracturing of a settled tradition. It seemed worth asking if Leigh would allow me to re-use the image. I didn’t know how to go about contacting him, but found an Ultravox fan-club website and asked the fan-club organiser if he could pass on a question; the answer came back indirectly that it would be okay, but that the image should be credited to John Foxx.

I had the 12″ single of ‘Slow Motion’, and though that would improve the image quality, but scanning an image that was slightly too large for any available flat-bed scanner proved to be a nightmare. (This was sometime in 2001). I had to scan it in two parts and then digitally piece them together, and more or less manually sharpen the edges of lines, pixel by pixel. Doing it this way gave me the opportunity to eliminate some of the scuff marks on my own copy, but at some point the labour expended went beyond reasonable and beyond enjoyable, and became more of a labour of love. Somewhere in the line of transmission the pointed corner at the top right was flattened, which is frustrating, and of course OUP were never going to reprint the image in colour; but on the whole I’m happy with how it worked out.