In July I enjoyed writing a blog a day about The Jazz Butcher’s songs. This is the first in a series about The Blue Aeroplanes, using mostly the same cues, though I don’t think I can sustain the rate of a blog-per-day. Like the Jazz Butcher series, after the first entry this will be arranged in approximately chronological order by the date the record was released.

#31Songs (1): The First One I Ever Heard

‘Tolerance’ by The Blue Aeroplanes

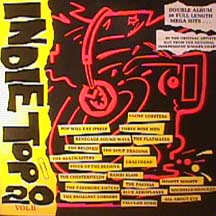

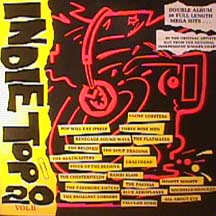

I first heard The Blue Aeroplanes on a cheap and cheerful compilation album I bought on vinyl around 1987 or 1988, the Beechwood Indie Top 20, vol.2.

The song on the album was ‘Tolerance’: this exists in at least three versions, and I’m not sure from memory which the compilers used, though I think it’s the one found on The Blue Aeroplanes’ Tolerance LP or the one on their Friendloverplane compilation. The Tolerance version begins with a melodic bass-line, and is sustained throughout by it, while the Friendloverplane version begins with delicate chiming guitars, and in the verses is altogether wispier than its Tolerance counterpart:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLoPuV2NLMI

There’s another later version with a more emphatic drum beat which turns up on the Warhol’s 15 compilation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tbb2z6ICYvM

‘Tolerance’ really stood out on the Indie Top 20 compilation. The Brilliant Corners’ ‘Brian Rix’ was funny but disposable; Michelle Shocked’s ‘If Love Was a Train’ had a bit more substance, and led me to her debut album (the proper debut rather than the Texas Campfire Tapes); but something about ‘Tolerance’ stayed with me: Gerard Langley’s spoken vocals; the contrasting, passionate, Johnny-Rottenish vocal on the chorus, which at the time I believed mistakenly to be Langley; the suggestion, within the dense and difficult lyric, that the singer was siding with the female protagonist (‘She should go out more and he should show some tolerance’); no vocal melody in the verses, of course, but all sorts of melodic suggestions in the guitars and in the bassline. All these were completely new to me. It stayed with me, but for some reason — lack of information in those pre-internet days, combined with a limited record-buying budget? — I didn’t follow it up and buy anything more by them.

On 5 December 1990 I bought the Friendloverplane compilation at the Our Price in the Westgate in Oxford — I tucked the receipt into the booklet, £11.99, and it’s still there — and learned that the chorus vocals were actually a guest appearance by Jedzrej Dmochowski, brother of Wojtek, the band’s dancer. I think by that stage I’d bought Swagger, which had come out in February 1990, and which I remember being heavily advertised on flyposters on hoardings outside Somerville. ‘Tolerance’ still stood out on Friendloverplane, but the compilation also gave an indication of the sheer range of their output in their first seven years: they’d first performed as The Blue Aeroplanes in 1981 (or so it says on Wikipedia); the compilation had come out in 1988. ‘Veils of Colour’ had some similar horn sounds, though more melancholy; ‘Severn Beach’ highlighted their skill at crafting a catchy chorus; ‘Etiquette’, had the same sceptical attitude as ‘Tolerance’ towards conventional gender relations, and a funkyish new wave feel to it; ‘Days of 49’ had Rodney Allen on vocals and showed off their folk side. There were samples, there was social protest, there were lyrics of baffling obliquity, there was a Bob Dylan cover. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

‘Tolerance’ isn’t an easy lyric to understand: we have glimpses and fragments of a narrative scenario, some or all of it seen in recollection, a time (‘that time’) in the past that the speaker is trying to measure and come to terms with. The splitting of the lyric between Gerard and Jedzrej adds a further interpretative problem: are we to understand this as some sort of duet, with Jedzrej replying to to Gerard’s lines, or is Jedzrej simply voicing a more passionate outburst on Gerard’s behalf? It has more characters than most love songs: there’s a woman at the centre of it, there’s a first person who is presumably, like the singers, male; there’s a him; and there’s a ‘you’ of uncertain gender who ‘said she looked older’ (an insult, a compliment, or a neutral comparison?), who gave her shelter, who cried on her shoulder, and who got lost and found. Heterosexual love-song convention would have ‘you’ be female, but it’s clear this is no conventional love song.

It could be a story of infidelities: that would be why she concealed him with her quick arms, and one way of thinking about the lamp being the mark of ‘something new’ is to picture it occurring late at night, the lovers suddenly illuminated by a streetlight, a new and unwelcome revelation. (There’s a scene like that in Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, and this song is every bit as cubist as Woolf’s novel). There’s a lot about light (punningly in ‘old flames’), and a line about wintry air: it’s a song of dark evenings and distrust. It’s also a song with hints of regrets: ‘it was me / Who said you should go there / And she should come along’. What were the consequences of the speaker’s saying ‘you’ should go there (where?) and her coming along? Did the ‘you’ and ‘she’ start a relationship in consequence?

In so far as it’s reflecting on that past history, it also asks what keeps people together: the need for shelter? something as abstract as ‘her intent’? And it asks at what point that becomes oppressively controlling: she should go out more? He should show more tolerance, the lyric says, though tolerance itself is still a controlling attitude.

And is it also weighing up relationships alongside the other things people fill their time with? Painting and art for example? Pass-times and ambitions? Are the ‘absentee notes’ lovers’ apologies, sardonically spoken of as it they were letters to one’s manager? And is the ‘X’ a signing-off kiss, or the manager’s dismissive cross?

‘And here we are again’, says Gerard with more than his usual weariness before the final chorus, and this seems both an admission that such situations repeat themselves (‘how we repeat these patterns’, as he says in another, later, song), but also a wry gesture towards the form of popular song in verses and choruses. An earlier song, ’20th Century Composites’, by an earlier incarnation of the band, Art Objects, had ended with the band singing ‘Verse chorus / Verse chorus / Middle eight / Solo’, so they have form in this regard. One of the oddities of ‘Tolerance’ is that the opening line seems to cast the events into a remembered past, but the present tense of other lines suggests that the situation is present: past and present can’t be kept so easily apart. The narrator would like ‘that time’ to be in the past, but like a chorus it keeps on coming round again. And these kinds of puzzle in the lyrics keep me coming back to it.

LYRICS

(Adapted from what I found at lyrics.wikia.com. I hear ‘flames’ where they have ‘flings’, and ‘pubs’ where they have ‘poems’.)

You could measure the effects of that time in light

A lamp could be the mark of something new

There were plants and frames and paintings invisible structure

She did conceal him with her quick arms

And her intent was the only thing that kept him there

And it was you

Who said she looked older

While it was me

Who stood by the door

But it was you

Who gave her the shelter

That she looked to him for

A worthwhile pass-time but a sad ambition

Absentee notes in the next room with X

She should go out more and he should show some tolerance

Ah, big ridicule such little thing

Such grip on everything we have

On everything we have

And it was you

Who cried on her shoulder

And it was you

Who got lost and found

And it was me

Who said you should go there

And she should come along

Our coat tails drag marks

Old flames don’t hold a candle

When the lights go out

at that civilised time

What do we have?

More pubs

The emptier the better

And events in the future

Like a state of undress

Through that wintry air

Kiss news down the line

And here we are again

And it was you

Who cried on her shoulder

And it was you

Who got lost and found

And it was me

Who said you should go there

But it was you who gave her the shelter